Executive Summary

A subsidy (also known as a subvention) is a form of financial assistance paid to an individual, a business or an economic sector in order to achieve certain policy objectives. For example, a subsidy can be used to support a service that cannot recover its full costs (e.g. through tariffs), which is a common problem in the water and sanitation sector. Subsidies may also be given to encourage activities that would otherwise not take place, e.g. a more sustainable sanitation technology. Subsides in developing countries flow almost exclusively from government, or via government in the case of official development assistance, and sometimes through international or national non-governmental organisations (EVANS et al. 2009).

Introduction

A subsidy (also known as a subvention) is a form of financial assistance paid to an individual, a business or an economic sector in order to achieve certain policy objectives. This means that any monetary exchange which is not directly connected to paying for a service can be defined as a subsidy. Financial assistance in the form of a subsidy may come from one's national or local government, but the term subsidy may also refer to assistance granted by others, such as individuals or non-governmental institutions, although these would be more commonly described as charity (ECONOMICS 2010).

In sanitation and water management, subsidies are very common, and many utilities have to be subsidised as they cannot recover the full costs of their services form the users (see also water pricing). This applies to services regarding water catchment, purification and distribution of fresh water, as well as the subsequent collection, treatment and discharge or reuse of wastewater (see also understand your system for more information on the whole cycle).

Also in agriculture, subsidies play a major role. For example, subsidies that reduce the price for artificial fertiliser (e.g. in India) also reduce the motivation and need of producers to use sanitation based fertiliser. Further, subsidies are often given to individual households in order to achieve certain policy objectives, such as achieving 100% sanitation coverage in a certain area.

Types of Subsidies in Sanitation and Water Management

(Adapted from FAO 2002)

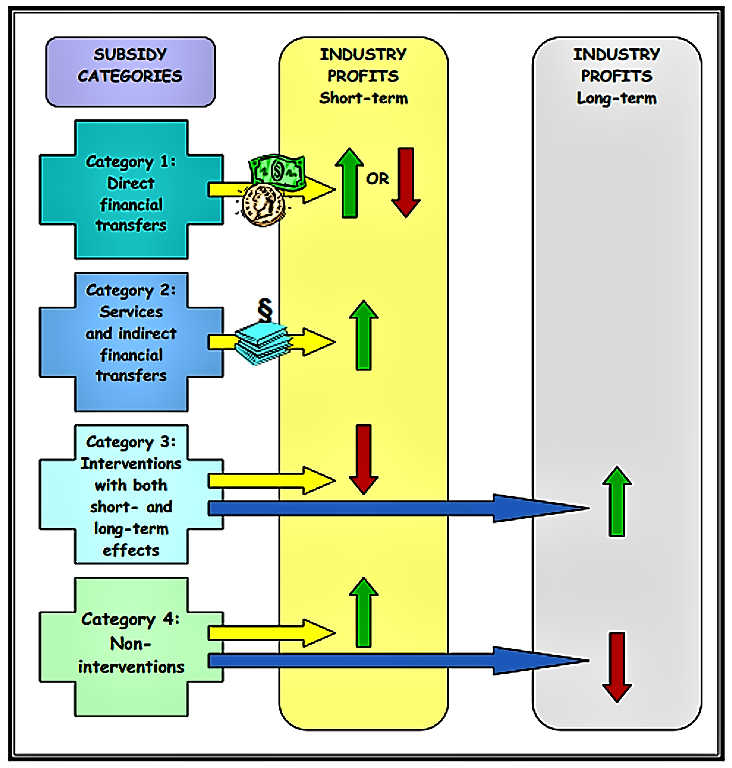

There are many different types of subsidies and ways to classify them, such as the reason behind them, the recipients of the subsidy, the source of the funds (government, consumer, general tax revenues, etc). Some typical subsidies in Sanitation and Water Management are:

Direct Subsidies: This type of subsidy is the simplest; this means directly giving money to people to achieve certain policy objectives by national or municipal government, national or international agencies or NGOs.

Examples of direct subsidies in the water sector are fore example funds which are used to cover part of the water bill of poor households who meet certain clearly defined eligibility criteria. Often, direct subsidies are also given in total sanitation campaigns to support people to build latrines to achieve an open-defecation free status in a certain area.

Services and Indirect Financial Transfers: The second category covers any other active and explicit government intervention but which does not involve a direct financial transfer as specified under the first category. This type of subsidies has a direct short-term effect on profitability but is rarely negative. Many of the subsidies in this category are services of some kind provided by the public sector or indirect financial transfers.

Examples of services and indirect financial transfers in the sanitation sector are the construction of community toilets which are provided by the municipal government for legal slum dwellers in order to reduce the open defecation within the city.

Interventions with Different Short and Long-Term Effects: The third category of subsidies allows considering a longer time perspective and includes government interventions that have a negative economic impact on the industry in the short-term but ultimately result in long-term benefits (for example the resource base) and/or more general benefits to society as a whole (for example the environment).

Some examples of category three subsidies within the water and sanitation sector are setting higher standards for treated wastewater (especially regarding BOD values). In the beginning these interventions will have a negative impact on the industries because they have to invest in better wastewater treatment, but in the long-term perspective, this intervention will have positive influence on the entire society.

Lack of Intervention: The last category covers the area of lack of government intervention and may be the most difficult one to deal with. This category comprises inaction on behalf of the government that allows producers to impose - in the short or long-term - certain costs of production on others, including on the environment and natural resources, and that has short-term positive effects on the industry’s revenues and/or costs. In this ways, the industries do not have to pay for services they would actually be supposed to pay for – so they indirectly receive an economic benefit.

These subsidies are usually positive in the short-term but negative in the long-term. By definition, they do not imply a direct cost to the government and their value to the industry is implicit.

Examples of this type of subsidies include: Lack of water pollution control, free access to water, non-implementation of existing regulations such as certain BOD regulation for treated wastewater from industries.

Controversies about Subsidies

One of the main problems with subsidies appears to be that the different objectives of any public subsidy remain non-explicit. Thus different observers may attach different levels of priority to different objectives. For instance, the main objective of a subsidy scheme might be to ensure inclusion and empowerment of certain disadvantaged groups but it might equally be to protect the environment or to improve public health. It may also be political (to raise votes). Clearly, in this situation the different observers are likely to have differing opinions about the success of the subsidy.

The ‘political’ objectives behind subsidies are particularly problematic. They are rarely made explicit to the public but can have a strong impact when dealing with improvement of finances. By implementing cost-intensive subsidies, government finances mostly suffer in return. It is probably the major reasons why the topic of sanitation and water subsidies is so problematic. In fact, in many countries subsidy is a highly politicised issue and it is essential to imply this objectives to the explicit ‘official’ objectives (EVANS et al. 2009). Free or highly subsidised water is often used as a campaign promise, for political gain. In India, for example, this has lead to the situation that the agricultural sector, which uses 90% of all water, received a large share of it for free. This political interference has been found to be a significant barrier to effective cost recovery.

Another difficulty which arises in terms of subsidies implementation within the water and sanitation sector is the lack of ownership that often occurs through these financial interventions and inappropriate integration of local communities. Many projects have failed in the past where water and sanitation infrastructure was constructed with subsidies from local government or international agencies but without sufficient integration and participation of local beneficiaries. The sustainability of the water and sanitation infrastructure which is constructed through subsidises can only be ensured if local community have a sense of ownership towards these new facilities which comes along with great acceptance and willingness to operate and maintain this newly constructed infrastructure. Otherwise, there is a high risk that the subsidised infrastructure, such as new toilets, is not going to be used by the local people.

Things to Consider before Using Subsidies

The design of subsidies needs to take into account not only current but also future considerations, and not only intended but also unintended consequences. The WSSCC/WHO (2005) programming guide publication lays out the following subsidies principles:

- Subsidies should achieve the intended policy outcome: Subsidies require a smart design and clarity about what the policy objectives are. Choices and tradeoffs need to be made between different interest groups, the wealthy and the poor, rural and urban populations and short- and long-term objectives.

- Subsidies should reach the intended target groups: They require clarity on who is the intended target group and how they can best be reached. It also requires rigorous monitoring to track how subsidies are reaching the intended groups.

- Subsidies should be financially sustainable: A solid understanding of the potential scale of needs and the costs of the programme is required. Costs include both upfront capital costs and long-term operational and maintenance costs even in rural areas. It also requires a good understanding of how to get the best possible increase in funding from other sources (typically households and market sources). Only on this basis can a sustainable financial regime be put in place.

- Subsidies should integrate local peoples’ needs: In order to guarantee the sustainability of the subsidised sanitation or water infrastructure, it is of prime importance to facilitate the integration and participation of the local beneficiaries and to develop a sense of ownership towards the new infrastructure.

- Subsidies should be implemented in a clear and transparent manner: Finally, since they involve the use of large sums of public money, subsidy programmes need to be clear and transparent, enabling eligible households or communities to access them and providing clear recourse mechanisms in cases where there is a suggestion of impropriety. Proper monitoring and evaluation is an essential element of such transparency and must be fully financed as part of the subsidy programme (EVANS et al. 2009).

Implementing Subsidies

(Adapted from FOSTER et al. n.y.)

In order to implement a subsidy scheme it is necessary to establish:

- a legal framework as a basis for the subsidy scheme

- an institutional framework charged with implementing the scheme

- a series of administrative procedures (including sound enforcement bodies) to govern the operation of the system

In the past, subsidy systems have often suffered from a lack of clarity regarding their objectives and a lack of transparency regarding their procedures. The absence of any clearly defined rules to govern the allocation of subsidies has meant that they have been managed with a high degree of discretion, primarily to further the political exigencies of the moment. It is therefore important that any subsidy system should be given a clear basis in law. This serves to strengthen the legitimacy of the subsidy programme and to ensure that funds are used in a socially effective manner. While it need not go into great detail, the law should at least establish the following points:

- the government institution with overall responsibility for the subsidy programme (see also: institutional framework)

- the potential sources of finance for the subsidy programme

- the basic principles that should be observed in administering subsidies

The main administrative procedures required to make the subsidy scheme operational are as follows:

- Budgeting procedure. This should incorporate a system for projecting the likely costs of the programme from one year to another, and should identify how any shortfall or surplus of subsidy funds should be dealt with.

- Selection procedure. This should establish the routes through which applications can be made, and the way in which they will be screened, as well as the process for reaching a final decision regarding eligibility for the subsidy.

- Payment procedure. This should clarify the way in which subsidy beneficiaries will be billed, and establish how and when funds will be transferred from the government to the concessionaire.

Example of Subsidies Applied in the Sanitation Sector: Total Sanitation Campaign, India

(Adapted from KHURANA et al. 2008; PATTANAYAK et al. 2009)

The Government of India has a nationwide total sanitation campaign (TSC) that seeks to change attitudes about latrines in individual households. TSC aims at improving the quality of life of people in rural areas through the creation of open-defecation-free and fully sanitised villages. It has been 11 years since the programme was launched in 1999. The campaign is designed as a demand-driven, community-led programme and is implemented by state governments. There is currently an emphasis on developing information, education and communication (IEC) activities to improve attitudes and knowledge about how sanitation, safe water and hygiene relate to health. The campaign also acknowledges the role of subsidies in encouraging the poor to construct individual household latrines.

The campaign has had a positive impact but certain changes are needed to make it more effective. It also brings out a number of interesting aspects related to the sector, like whether a subsidy should be given to construct a toilet, or whether offering incentives for attaining total sanitation will work more effectively in the future.

A highly debatable issue has been that of subsidies to individual households for construction of toilets. Experts disagree as to whether improved access to sanitation and other health technologies is better achieved through monetary subsidies or shaming techniques (i.e. emotional motivators).

In fact, the TSC guidelines do not use the term ‘subsidy’; the money given to households is called an ‘incentive’. According to the guidelines, the money is available only for below poverty line households.

Although many people back the idea of offering a subsidy, a survey carried out by the Indian Institute of Mass Communication found that only 2% of respondents agreed that a subsidy was motivation to construct a toilet; 30% were motivated by convenience; and 21% by the idea of privacy that a toilet in the house offers. What was significant was that 40% of rural households were willing to contribute around Rs 500 towards construction of a toilet; 20% of households were willing to pay more. These findings appear to contradict the belief that subsidies are the main motivating factor in toilet construction and that people are willing to contribute financially in order to have a sense of ownership towards the sanitation facilities. However, depending on the chosen technology and its arising costs, subsidies might be a precondition for some people to opt for a more expensive, but also more sustainable alternative.

Subsidies can be a powerful (but also expensive) tool to optimise the sanitation and water management system and make it more sustainable in the long run. Subsidising more expensive, but also more sustainable sanitation or water management technologies is a typical example where subsidies can be utilised to achieve higher sustainability.

Subsidies can be positive for water management and sanitation, since the price relations between different options (higher or lower emission levels, more or less energy intensity, more or less transport) can be modified in favour of the environment.Independent of the type of financial assistance, subsidies should always be applied in the public interest to maximise health benefits and increase access specifically to groups who are persistently excluded within the water and sanitation sector. Furthermore, it is important to base subsidies on solid and rigorous information about what types of service people want and are willing-to-pay for, what the affordability for the target group is, and what can be scaled up in the long term (WSSCC 2005).

In order to avoid distortions to the market, one should subsidise the lowest possible level of water and sanitation service and better leave room for subsidies to make incremental improvements over time.

Search Economic Terms: Subsidy

Public Funding for Sanitation. The many Faces of Sanitation Subsidies

This is a publication describing the different faces of subsidies. However, it is mainly written from the sanitation point of view.

EVANS, B. VOORDEN, C. van der PEAL, A. (2009): Public Funding for Sanitation. The many Faces of Sanitation Subsidies. Geneva: Water Supply and Sanitation Collaborative Council URL [Accessed: 29.04.2019] PDFExpert Consultation On Identifying, Assessing And Reporting On Subsidies In The Fishing Industry

Infrastructure Reform, Better Subsidies, and the Information Deficit

This note discusses the type of information required to design adequate subsidies, where it can be found, and ways to deal with lack of available data to design subsidies.

GOMEZ-LOBO, A. FOSTER, V. HALPERN, J. (2000): Infrastructure Reform, Better Subsidies, and the Information Deficit. Washington DC: The World Bank URL [Accessed: 29.04.2019]Subsidy Estimation: A survey of current practice. International Institute for Sustainable Development Global Subsidies Initiative

A Typology of Tools for Building Sustainability Strategies

Since the 1980s, the Swiss federal government has actively pursued a policy to reduce the emission of pollutants from heating systems. The program bases upon three measures, which are regulatory in nature: emission thresholds, systems inspections with permits and heating controls.

KAUFMANN-HAYOZ, R. BAETTIG, C. BRUPPACHER, S. DEFILA, R. DI GIULIO, A. FLURY-KLEUBER, P. FRIEDERICH, U. GARBELY, M. JAEGGI, C. JEGEN, M. MOSLER, H.J. MUELLER, A. NORTH, N. ULLI-BEER, S. WICHTERMANN, J. (2001): A Typology of Tools for Building Sustainability Strategies. In: KAUFMANN-HAYOZ, R. ; GUTSCHER, H. (2001): Changing Things – Moving People. Strategies for Promoting Sustainable Development at the Local Level. Basel: 33-108. URL [Accessed: 29.04.2019]India's Total Sanitation Campaign: Half full, half empty

A soon-to-be released WaterAid India review of India’s Total Sanitation Campaign in five states finds both positives and negatives in the ambitious programme. It also raises some serious questions about sustainability. It found out that subsidies can overcome serious budget constraints but are not necessary to spur action, for shaming can be very effective by harnessing the power of social pressure and peer monitoring. Through a combination of shaming and subsidies, social marketing can improve sanitation worldwide.

KHURANA, I. MAHAPATRA, R. SEN, R. (2008): India's Total Sanitation Campaign: Half full, half empty. Pune: InfoChangeWater, Electricity, and the Poor: Who Benefits from Utility Subsidies?

This book systematically examines the targeting performance of consumer utility subsidies in 32 programs from 13 water utilities as well as a similar sample of electricity utilities. Most of the programs involve volume-based subsidies, which are common in the water sector.

KOMIVES, K. FOSTER, V. HALPERN, J. WODON, Q. (2005): Water, Electricity, and the Poor: Who Benefits from Utility Subsidies? . Washington DC: The World Bank URL [Accessed: 29.04.2019] PDFShame or subsidy revisited: social mobilisation for sanitation in Orissa, India

This study aimed to determine the effectiveness of a sanitation campaign that combines “shaming” (i.e. emotional motivators) with subsidies for poor households in rural Orissa, an Indian state with a disproportionately high share of India’s child mortality.

PATTANAYAK, S. K. ; YANG, Y. C. ; DICKINSON, K. L. ; POULOS, C. ; PATIL, S. R. ; MALLICK, R. K. ; BLITSTEIN, J. L. ; PRAHARAJ, P. (2009): Shame or subsidy revisited: social mobilisation for sanitation in Orissa, India. In: Bull World Health Organ 2009: Volume 87 , 580–587. URL [Accessed: 03.09.2010]Sanitation and Hygiene Promotion: Programming Guidance

Infrastructure Reform, Better Subsidies, and the Information Deficit

This note discusses the type of information required to design adequate subsidies, where it can be found, and ways to deal with lack of available data to design subsidies.

GOMEZ-LOBO, A. FOSTER, V. HALPERN, J. (2000): Infrastructure Reform, Better Subsidies, and the Information Deficit. Washington DC: The World Bank URL [Accessed: 29.04.2019]Water, Electricity, and the Poor: Who Benefits from Utility Subsidies?

This book systematically examines the targeting performance of consumer utility subsidies in 32 programs from 13 water utilities as well as a similar sample of electricity utilities. Most of the programs involve volume-based subsidies, which are common in the water sector.

KOMIVES, K. FOSTER, V. HALPERN, J. WODON, Q. (2005): Water, Electricity, and the Poor: Who Benefits from Utility Subsidies? . Washington DC: The World Bank URL [Accessed: 29.04.2019] PDFPublic Funding for Sanitation. The many Faces of Sanitation Subsidies

This is a publication describing the different faces of subsidies. However, it is mainly written from the sanitation point of view.

EVANS, B. VOORDEN, C. van der PEAL, A. (2009): Public Funding for Sanitation. The many Faces of Sanitation Subsidies. Geneva: Water Supply and Sanitation Collaborative Council URL [Accessed: 29.04.2019] PDFWater Subsidy Design: Implications and Consequences

The main question that this paper tries to answer is “How should water be priced by a state water company in poor developing country?” This is a critical paper where the economic arguments for and against subsidised water are critically developed.

MENG, J. (2008): Water Subsidy Design: Implications and Consequences. URL [Accessed: 29.04.2019]Water as an Economic Good and Demand Management. Paradigms with Pitfalls. International Water Resources Association

This paper argues that water pricing should primarily serve the purpose of financial sustainability through cost recovery. Instead of economic pricing, there is a need for defining a reasonable price, which provides full cost recovery but which safeguards ecological requirements and access to safe water for the poor.

SAVENIJE, H. ; ZAAG, P. van der (2002): Water as an Economic Good and Demand Management. Paradigms with Pitfalls. International Water Resources Association. In: Water International: Volume 27 , 98–104. URL [Accessed: 22.04.2019]Designing Direct Subsidies for the Poor — A Water and Sanitation Case Study

Short case study about how direct subsidies are an increasingly popular means of making infrastructure services more affordable to the poor in Chile. Under the direct subsidy approach, governments pay part of the water bill of poor households that meet certain eligibility criteria.

FOSTER, V. GOMEZ-LOBO, A. HALPERN, J. (2000): Designing Direct Subsidies for the Poor — A Water and Sanitation Case Study. Washington DC: The World Bank URL [Accessed: 29.04.2019]Infrastructure Incentive-Based Subsidies. Designing Output-Based Subsidies for Water Consumption

This is a paper which shows how to guarantee adequate and affordable water and sanitation services for vulnerable households. In the example of Chile, where the public authorities determine how the subsidy is applied, but mostly private companies deliver the service — under a scheme with built-in incentives to ensure cost-effective service delivery by the companies and low wastage by the customers.

GOMEZ-LOBO, A. (2001): Infrastructure Incentive-Based Subsidies. Designing Output-Based Subsidies for Water Consumption. Washington DC: The World Bank URL [Accessed: 29.04.2019]India's Total Sanitation Campaign: Half full, half empty

A soon-to-be released WaterAid India review of India’s Total Sanitation Campaign in five states finds both positives and negatives in the ambitious programme. It also raises some serious questions about sustainability. It found out that subsidies can overcome serious budget constraints but are not necessary to spur action, for shaming can be very effective by harnessing the power of social pressure and peer monitoring. Through a combination of shaming and subsidies, social marketing can improve sanitation worldwide.

KHURANA, I. MAHAPATRA, R. SEN, R. (2008): India's Total Sanitation Campaign: Half full, half empty. Pune: InfoChangeShame or subsidy revisited: social mobilisation for sanitation in Orissa, India

This study aimed to determine the effectiveness of a sanitation campaign that combines “shaming” (i.e. emotional motivators) with subsidies for poor households in rural Orissa, an Indian state with a disproportionately high share of India’s child mortality.

PATTANAYAK, S. K. ; YANG, Y. C. ; DICKINSON, K. L. ; POULOS, C. ; PATIL, S. R. ; MALLICK, R. K. ; BLITSTEIN, J. L. ; PRAHARAJ, P. (2009): Shame or subsidy revisited: social mobilisation for sanitation in Orissa, India. In: Bull World Health Organ 2009: Volume 87 , 580–587. URL [Accessed: 03.09.2010]Micro-irrigation Subsidies in Gujarat and Andhra Pradesh

Despite its proven benefits, micro-irrigation has been slow to realise its potential in India. Following the recommendations of the Micro-irrigation task force in 2004, a tiered set of subsidies was put into place for micro-irrigation. The models set up in Andhra Pradesh and Gujarat have been considered the most successful. This paper compares these two models using several parameters and comes up with a set of recommendations for replication elsewhere.

PULLABHOTLA, H.K. KUMAR, C. VERMA, S. (2009): Micro-irrigation Subsidies in Gujarat and Andhra Pradesh. Implications for market dynamics and growth. (= Water Policy Research Highlight , 43 ). Gujarat, India: IWMI-Tata Water Policy Program URL [Accessed: 15.01.2013]Domestic Water Pricing with Household Surveys: A Study of Acceptability and Willingness to Pay in Chongqing, China

This study shows that a significant increase in the water price is feasible as long as the poorest households can be properly subsidised and certain public awareness and accountability campaigns can be conducted to make the price increase more acceptable to the public.

WANG, H. XIE, J. LI, H. (2008): Domestic Water Pricing with Household Surveys: A Study of Acceptability and Willingness to Pay in Chongqing, China. Washington DC: The World Bank URL [Accessed: 22.04.2012]Producer Subsidies (Government Intervention)

This is a web tutorial which describes subsidies from the economical point of view.

The IISD Global Subsidies Initiative (GSI)

The International Institute for Sustainable Development’s Global Subsidies Initiative (GSI) is a project designed to put the spotlight on subsidies and the corrosive effects they can have on environmental quality, economic development and governance.

Aguanomics - The political economy of water and other distractions

A blog from an economist with different opinions related to water and economy.